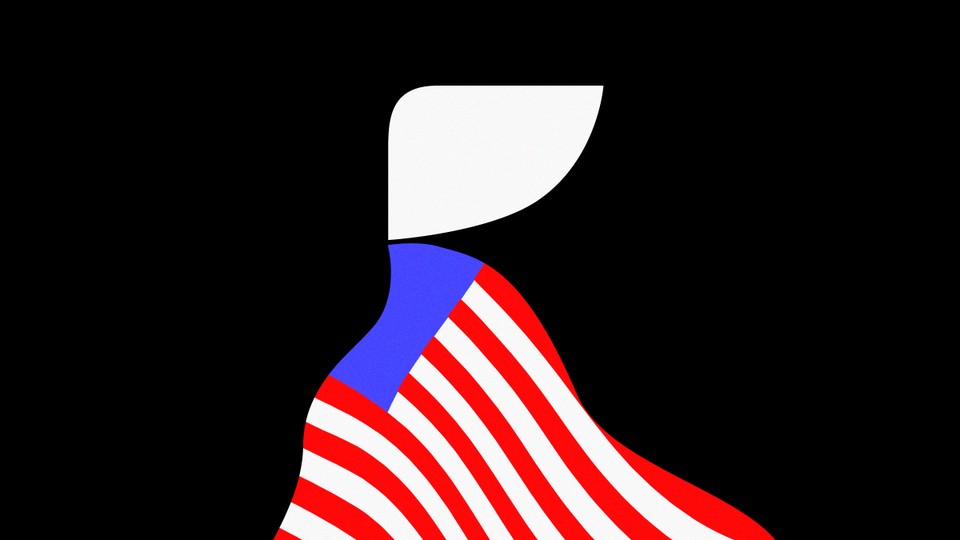

Slouching Towards Gilead

In June 2019, Kylie Jenner shared with the world some pictures of a birthday party she’d thrown for a friend. The event had a theme: The Handmaid’s Tale. It featured guests garbed in blood-red gowns; servers dressed as “Marthas,” or women enslaved for household labor; and drinks with such names as “Under His Eye tequila” and “Praise Be vodka.” The whole thing was cringey and absurd. It was also, as so often happens when the extended Kardashian family is involved, grimly eloquent. One of the lessons of The Handmaid’s Tale is the ease with which horror can become a habit. In a culture that is adept at turning tragedy into comedy, even the darkest of dystopias might be consumed, in the end, as a signature cocktail. Banality has its allure.

When the TV version of The Handmaid’s Tale premiered in 2017, the show was a textbook piece of Trump-era resistance art—a direct reply to the preening misogynies of the newly elected president. Both the book and the show were timely parables of gendered violence, reminders that history can also move backwards. And they retain that power today: The Trump administration may have concluded, but its encroaching cruelties have not. State leaders are currently attempting to legislate away the rights of, among many others, trans people, of other LGBTQ people, of women. But The Handmaid’s Tale is urgent again for another reason as well. Lawmakers in several states, empowered by the nearly friction-free spread of Trump’s Big Lie, are attempting to limit people’s ability to vote—and building the power to cast as “fraudulent” those electoral outcomes they find politically inconvenient. They are doing much of this in a way that might be familiar to Atwood’s readers: They are treating these elemental threats to democracy as if they were business as usual.

[Read: American cynicism has reached a breaking point]

“This may not seem ordinary to you now, but after a time, it will,” Aunt Lydia, whose job is to indoctrinate young women into the ways of Gilead, assures her charges. “It will become ordinary.” She means this as a promise, but in truth, it is a threat. Gilead, like many of the real-world regimes that inspired it, uses ordinariness as a tactic of oppression. Much of its propaganda is aimed not at angering people, but at soothing them. Its invented language is strategically casual. In this world, ritualized rapes are known as “ceremonies”; murders of dissidents are dismissed as “salvagings”; violence is made so routine that it becomes unremarkable. In a story full of villains, ordinariness is its own kind of enemy.

The book’s narrator, Offred, understands that. She expends much of her energy simply resisting the urge to see what is happening to her and around her as anything but horrific—anything but shocking. This is one form of resistance: Nolite te bastardes carborundorum. Don’t let the bastards grind you down. The regime that has conquered much of America in The Handmaid’s Tale takes advantage of the fact that, in times of crisis, people’s desire for normalcy can be so deep that it can easily edge over into complacency. “The new normal,” in this universe, is not a cliché. It is a concession.

The fourth season of the TV series—its finale is now streaming on Hulu—has also been a meditation on normalcy’s empty promises. Many of the show’s main characters have at this point come to live outside Gilead, in Canada, either as refugees (Moira, Emily, Rita) or as prisoners (Serena, Fred). Each is trying to adjust to their new circumstances, whether to freedom that has been newly reclaimed or to freedom that has been newly constrained. The effort is not easy for any of them; Gilead’s horrors are portable. Trauma obeys no borders. In an earlier season of the show, June orchestrated the rescue of several children from Gilead. Now, their new caretakers learn, some of those kids are missing the lives they’d had under the regime. The adults struggle to make peace with young people who are ambivalent about their own salvation. The show’s fourth season has been asking, essentially, whether true normalcy is possible in a world where Gilead still exists. This question culminates in a brutal, full-circle finale. Its violence suggests that the answer is no.

[Read: The ‘pussy’ presidency]

“There was little that was truly original about Gilead,” the coda to the novel, a retrospective academic presentation about the workings of Gilead, observes. “Its genius was synthesis.” You might say something similar about the novel itself. It is powerful in part because its fictions flow from the hard facts of history: Atwood’s story blends lessons from Iran’s theocratic revolution, from Nazi propaganda, from the perfunctory playbook of 20th-century autocrats. But some of the book’s deepest insights are human-scaled. Atwood pays a lot of attention to the fact that Offred spends much of her time as a victim of Gilead merely … bored. “There’s time to spare,” Offred notes. “This is one of the things I wasn’t prepared for—the amount of unfilled time, the long parentheses of nothing.”

The Handmaid’s Tale, as a TV show, can sometimes read as a victim of its own success: Renewed for a second season, and then a third, and then a fourth, the series has been required to expand its story far beyond the material of Atwood’s novel. The broadened mandate has occasionally served the project. The show has deepened the backstories for several of its supporting characters. But the careful world-building of the first season has also ceded ground to the needs of melodrama. This is true especially when it comes to the show’s portrayal of violence. Season 4 has depicted a rape and a stabbing and, yes, a waterboarding. Is such brutality instructive or exploitative? When the violence is normalized, the question becomes moot. The viewer might simply end up doing what Offred, in the book, tries so hard to resist, and become desensitized to it all.

[Read: What the sexual violence of ]‘Game of Thrones’ begot

Shock is a finite resource, for TV shows and their audiences alike. “Shocking but not surprising” was one of the truisms of the Trump era, a means of conveying how readily his aberrant—and often abhorrent—behavior had been normalized. Trump proved that shamelessness can work as a smoke screen. Other politicians have learned that lesson. Earlier this month, a group of democracy scholars produced a joint statement of concern about threats facing the American electoral system. As of this writing, nearly 200 experts have signed it. “We … have watched the recent deterioration of U.S. elections and liberal democracy with growing alarm,” they wrote. They cited in particular Republican-led efforts to pass laws that

could enable some state legislatures or partisan election officials to do what they failed to do in 2020: reverse the outcome of a free and fair election. Further, these laws could entrench extended minority rule, violating the basic and longstanding democratic principle that parties that get the most votes should win elections.

Many of these affronts to election integrity are being enacted, in the name of preserving election integrity. They are extensions of Trump’s Big Lie. They are systematic. “We did it quickly and we did it quietly,” Jessica Anderson, the executive director of Heritage Action for America, a sister organization of the Heritage Foundation, told donors about voter-suppression measures that the Iowa legislature had passed in February. She described the template the firm had produced that served as a model for Iowa’s and other state-sponsored voting restrictions. The overall effort, she suggested, had been remarkably straightforward. “Honestly, nobody even noticed,” she said. “My team looked at each other and we’re like, ‘It can’t be that easy.’”

It can be that easy. It should not be that easy. One of the paradoxes of this moment of democratic emergency is that the threat, strictly speaking, doesn’t always look like the crisis it is. Laws being passed by lawmakers: This would seem to be business as usual. The whole thing is, for the most part, very orderly. Part of the challenge, for the public, will be to see the emergency for what it is—even if the encroachments are bureaucratic rather than outwardly violent, and even if the changes come slowly before they come suddenly. There are many ways to attempt a coup. And there are many ways for the unthinkable to become, finally, banal.