LONG STORY SHORT: The Original Beatnik Chick

It’s 1949.

It’s 1949, a worldwide war has ended, and everything is different than it’s ever been before. Everything is different than it will ever be again. Nothing is ever going to be the same.

More from Spin:

- Marcus Strickland: Sax Machine

- JOHN MELLENCAMP, PAINTER

- Defending Free Speech Is a Dirty Job But Someone’s Gotta Do It: Talking the First Amendment with Nico Perrino of FIRE

Now it’s no longer 1949. It’s now. Every goth-inclined girl glaring deep into her mirror, deadly focused as she darkens her eyes, looking out from beneath blackened eye-lines, owes a debt, is paying homage, is starting fresh from an aftermath. Carefully, precisely, outlining, flourishing, filligreeing, they echo the lines of Juliette Gréco, someone they don’t know, a voice they’ve never heard. Juliette Gréco: the original beatnik chick, from before there were even beatniks.

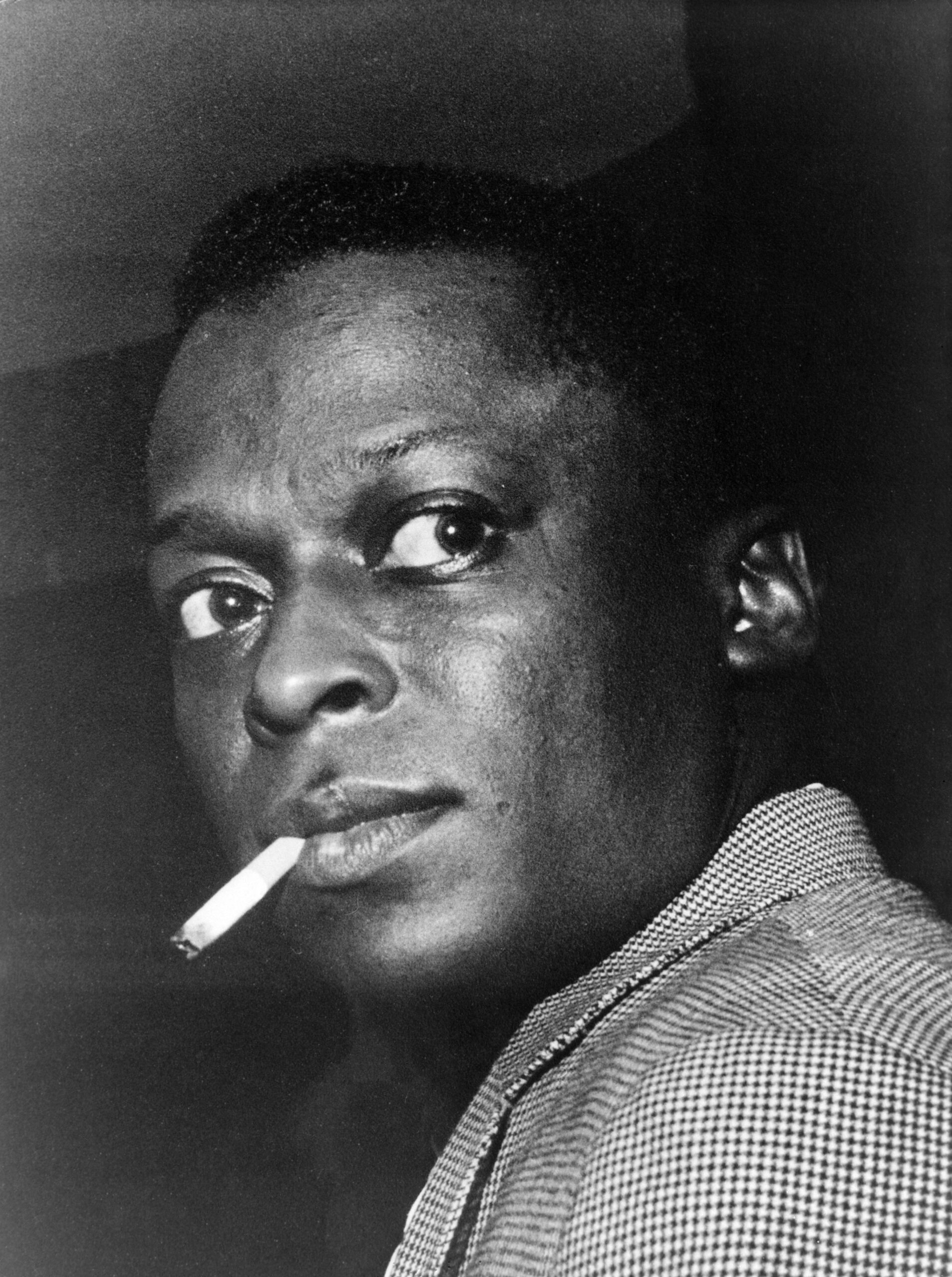

It’s 1949, and Miles Davis is touring Paris when he has a moment of recognition, of realization: He is — as now he suddenly sees, suddenly feels, suddenly transubstantiates into — Miles.

The Miles who from this instant on through decade upon decade rises up and reinvents himself, while always being immutably and immutably always Miles.

It’s a self-realization, a self-recognition, sparked here, now, in Paris 1949, that happens more than any other reason because he falls in love with the bohemian princess of Paris.

Juliette Gréco sends out a signal that girls across the decades, to this very moment, keep receiving, as if by magic, by silent radio waves, by top-secret coded transmission from le Resistance, yes, unquestionably — but sent from a Resistance of a different kind. She is what every troubled teen girl can barely dare fantasize becoming. At 11, she lives the disciplined daily nightmare of every little girl’s dream: She is a ballerina at the Opera Garnier in Paris. Then her city is occupied, she punches a Nazi in the nose, is sent to Fresnes Prison, a place of torture and executions. Released in sandals and a nightdress, she walks across wintry Paris to Gestapo headquarters to demand her possessions. Her mother and sister are gone, correctly suspected of being of the Resistance, sent to the concentration camp at Ravensbruck. Food doesn’t exist; she smokes cheap pipe tobacco to control her hunger. That smoke and the hunger it hides will live in her music.

In the aftermath, she’s the dark-eyed jeune fille invited to sit with the smoking philosophers and the dreaming songwriters, who pull her aside to offer their finest gifts, their deep thoughts and new songs, and maybe a meal afterwards. She sits with Pablo Picasso and Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre. Photographers Robert Doisneau and Henri Cartier-Bresson, whose pictures focus the epoch, politely ask to shoot her portrait. She sings in the caves, the cellars of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, sings strange new chansons written in this strange new moment. Songs arrive, are made hers, then made Parisian, then become international, songs from Jacques Prévert, Léo Ferré, Georges Brassens, from Serge Gainsbourg, Yves Montand, et Jacques Brel. These are strange songs, small things, songs of death and decay, of love unknown or only just remembered, of rhythms felt but never danced. These are songs that need the existence of a Juliette Gréco to form themselves, to spring to life. She astonishes her little audiences more than she could be said to entertain them. There’s no real money in it. There’s only more poverty, but Paris is free, she’s free, and there are strange new songs, songs like never before.

It’s 1949.

Miles Davis arrives for the Paris International Festival du Jazz. It’s May. He’s 22. If the weather is ever nice in Paris, your bet is on May. The Occupation is over — yes, we’re short a few Jews, but we weren’t terribly fond of them in the first place, and new apartments are always so difficult to find. The gendarmes gathered the Jewish children from the schools in order to hand them over to the Nazis, who worried that the French were too enthusiastic. Past that minor unpleasantness, if you’ve survived, it’s May in Paris, and bebop is brand new. It’s 1949.

The ultra-enthusiastic French announcer simply can’t help himself, can’t stop enthusiastically announcing, can’t quit — Miles is getting pissed! — explaining about the meaning and practice and profound Mozartian polyphonics underlying the aesthetic meaning of le nouvelle jazz bebop, enthusiastically announcing — Fuck this! Miles kicks off the tune — the stellar line-up, which is stellar: James Moody on tenor sax, Tadd Dameron on piano, and the spectacular bomb-dropping bop drum pioneer Kenny “Klook” Clarke. The more Monsieur Enthusiasme announces, the more Miles starts riffing over top of him, quick and loud, trying to get the connard to shut the fuck up. At last he does shut up, momentarily, until the next number, when he grabs the mic to introduce every single member of the band all over again, until Miles shrills him away, scatters the chatter as if his trumpet were one of the green brooms that sweep the gutters of Paris each evening.

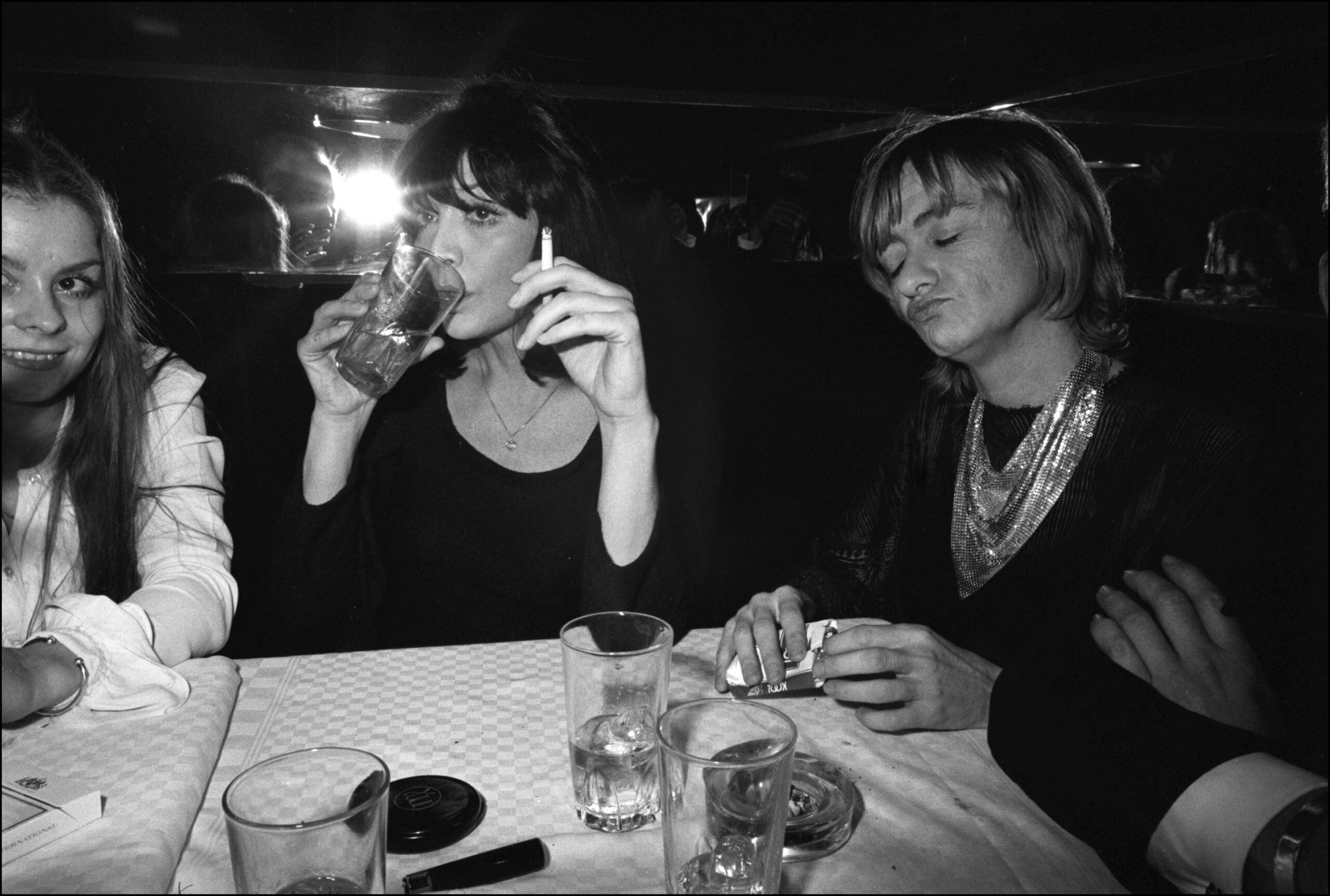

It’s 1949, and Juliette Gréco is at the Festival International, of course. Consider how absurdly hip she is! The proto-beatnik chick, dressing in men’s cast-offs — black sweater, tight black slacks, black flats, black bangs, black eyeliner, deep dark blue-black life experience even at 22, and smitten, as you would be, ought to be, must be, by the young Miles Davis, just 22 as well, the most handsome man in the world, and high among the most instantly recognizable stylists in all the history of jazz, then or now or before or later. A Negro too, in this time of liberation from the Nazi’s absolute banishment of jazz, a mongrel Negro non-art that caused even good German goose-stepping feet to tap furtively — and naturally resulted in rebellious French teenage zazous, defiantly hep hipsters, hiding and hoarding their jazz 78s, rolling the carpets back in furtive apartments to dance in daring defiance, in exuberant defiance of Nazis and neighbors and the oppressively normal. And yet Juliette Gréco was no zazou — no swing records in concentration camps, nor rugs to roll back — and it’s 1949. Paris is a battered place of freedom, self-invention, cigarettes, and deep talk that springs from dark-eyed experience.

Jean-Paul Sartre, unrivaled King of the Cafe du Flore, has set her up with a convenient room down the hall from his own at the Hotel La Louisiane; Simone de Beauvoir’s room is on another floor. We’re not being rude but just a bit French when we peek at the photos of Gréco’s tousled head leaning from bed, records and saucers strewn everywhere, to flip the tunes on her phonograph on the floor. She and Miles communicate with body language, gestures, kissing, eyebrows, sex, and with music. They are seen holding hands as they walk along the Seine. Witness the birth of the cool. It’s 1949 and they’re both 22, they’re both in love. Miles, married with kids at home in the States, will reflect, late in life: “Juliette was probably the first woman I loved as an equal human being.”

Consider this love affair, this lifelong love affair, which it unquestionably was. And then imagine how extraordinary she is as an artist, as a singer, as a musician, to not become some horrifying French jazziste but rather to carry on in her own mode, a supremely French chanteuse, and to have a far greater influence on Miles’ own languorous time, the most bone-dry time in modern jazz. Because here’s the shocking fact: Miles Davis, most daring of innovators, was even more influenced by Juliette Gréco’s aesthetics than she was by his.

They were in love, and faithfully remained so through life and other marriages, other affairs. How French of him — and of her, bien sur! But the wordless love of an equal human being — think on it for a moment. Hotel La Louisiane was a refuge for Negro jazz musicians, for Dexter Gordon and Bud Powell, for Billie Holiday and Lester Young, for Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and John Coltrane, but Paris itself was a refuge for American Negros, for writers like James Baldwin, Richard Wright, Langston Hughes, for musicians and artists and for any of the less-talented nine-tenths who could work their way loose of America to land in Paris, where the closer they lived to the Metro stop at Chateau Rouge, the more likely they were to be mistaken as coming from some exotic colony in Africa. And in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, a black American man could walk hand in hand with a white French woman, love one another beyond words, each an equal human being. It’s 1949, and everything is different than it’s ever been before.

It’s 1949. In time, it ceases being May. Miles returns home, Juliette Gréco stays in Paris. It’s 1949 in the United States, a worldwide war is over, and in America there would be no walking hand in hand for them no matter where they walked, no matter where they went. Miles will spend the next few years darkly depressed, shooting dope, trying to kill time. He hustles and pimps and shoots more dope. Juliette will achieve many lovers, gather even more admirers, and be the astringent voice of strange new songs that speak of age, regret, parted lovers, dead leaves blown in cold winds, songs of love and hope blooming under clam-broth-colored skies, sung in argot, en verlan et Javanaise, the street slang of Parisian criminals.

Something in her voice transcends her striking looks. Something in her songs strips away affectation. This is no cabaret singer, pleading for your laughter and begging for your tears. This is why songwriters bring her dry-eyed, dark-eyed chansons, these modern melodies with words that wound you, but only when you hear them the next morning as you wake from dreams and see the blood.

It’s no longer 1949. It’s the long now of Miles — a now that is Juliette Gréco’s gift to the man. Far from Paris, he hears. He hears exactly everything. Miles never doesn’t sound like Miles, never again needs to kill time — time is Miles Davis’ servant. His song is dry-eyed, astringent, dark-eyed, never pleading, never begging for your tears, stripped of affectation. Their love affair continues, lasts until he dies. They only ever hold hands again in Paris.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.

The post Defending Free Speech Is a Dirty Job But Someone’s Gotta Do It: Talking the First Amendment with Nico Perrino of FIRE appeared first on SPIN.