A Revolutionary Article (Part 1)

Hooray for the Red, White and Blue! Well, actually, we’ve had a lot better years than this to cheer about in the past, so it seems appropriate to take a stroll down memory lane along our animation trail to witness how past generations remembered their founding fathers. As most fireworks displays are canceled this year, we’ll instead highlight the historical aspects of the holiday, with concentration upon the Revolutionary War period, and an occasional nod to Abe Lincoln’s preservation of the Union in the process.

During the early years of animation, the historical epic does not appear to have been a mainstay of genres for most studios. Travels back in time were either of the extreme variety (all the way back to the stone age) or short voyages to the recent past (WWI remembrances), with an occasional venture to the Roman or Greek Empires such as Cubby Bear’s salute to “Ben Hur”, Porky Pig’s battle with the Gorgon, or the appearance of Nero in MGM’s Art Gallery. Our own revolutionary days were not generally treated as animation fare. Perhaps writers or executives thought audiences might be a little up tight with lampooning the figures that grade schoolers were being carefully taught to idolize with reverence. Perhaps also the combination of the impact of the Great Depression and rising unrest in Europe made any poking fun at our system of government feel a bit risky and unpatriotic. Not until the War in Europe first brought about mixed reactions from the male U.S. population at peacetime conscription, and the raucous atmosphere of Tex Avery and Bob Clampett-style humor graced the screens, did American historical figures start to appear periodically for a smile or two in pen and ink form. It can further be safely said that, until very recent years, unlike the broad and caustic satirical portrayals of our nation’s enemies during WWII, most American icons were generally treated in gentle form, with a degree of polite respect.

One of the earliest appearances of George Washington in animation I’ve encountered is Max Fleischer’s Betty Boop’s Birthday Party (Paramount, 4/21/33 – Dave Fleischer, dir./Seymour Knietel/Myron Waldman, anim.). The film itself is a typical (but spirited) random string of gags at a birthday party, with virtually no plot except for the animal guests getting into a no holds barred food fight. Betty (whom IMDB misattributes here to Mae Questal, while Wikipedia assigns to the more likely voicing of Kate Wright) paces back and forth atop a large table, pleading for her guests to behave themselves, when a blow to the table flips her off the opposite end into the air. She lands in the middle of a yard fountain with a marble statue in the center entitled, “Crossing the Delaware”, depicting George Washington and his crew in a rowboat. Betty lands directly behind the figure of Washington. The statue comes to life, turning its head to say, “Greetings, Betty.” Boop throws an arm affectionately around his neck. “Same to you, Georgie”, she replies. George issues a command to his crew: “Row”, and the entire statue proceeds off its pedestal, taking Betty and crew in an exit stage left. Several fish hop out of the fountain and converge on the pedestal, immediately launching into gossip session about Georgie and Boop, for the iris out. Political scandal in his first cartoon!

Certainly the granddaddy of all patriotic cartoons is Old Glory (Warner, Merrie Melodies (Porky Pig), 7/1/39 – Charles M. (Chuck) Jones, dir.). In the previous year, Leon Schlesinger had okayed at least one other unusual project – a sort of cartoon adaptation of the popular Warner live-action jazz/swing musical shorts typically billed as “Broadway Brevities”, which became Hardaway and Dalton’s Katnip Kollege (1938) – complete with borrowed vocal outtakes from live-action feature, Over the Goal. In 1939, an executive decision (Schlesinger’s or some higher-up studio head?) was somehow made to adapt to the cartoon medium a second genre of Warner live-action short, which had been developing increasing notice for a few seasons through its lavish dramatic portrayals and innovative use of three-strip Technicolor – the patriotic historical short. These shorts became a unique signature to Warner’s output in the years before WWII, and were lavishly budgeted and staged (reputedly losing the studio over $1.5 million, yet raking in the prestige of several Oscars). If it could work in live action, why not cartoons? Well, if anyone had actually asked this question, the answer might have been obvious – because truly historical films are not funny. Humorless cartoons telling tales of straight adventure were still a few years away – so the idea of such a project must have seemed to many of the animators like placing the proverbial fish out of water. (Imagine the reaction if such a film had been saddled upon Tex Avery!) As produced, the film takes itself entirely seriously, and (with the possible exception of the independently-produced “The Door” in the final years of Warner cartoon distribution), is the only Warner cartoon ever to contain not so much as a single laugh or chuckle. Accordingly, the project was assigned to the Warner director who, at this time in the fledgling stage of his career, was least associated with laughs and most associated with Disney-quality draftsmanship – Chuck Jones.

Certainly the granddaddy of all patriotic cartoons is Old Glory (Warner, Merrie Melodies (Porky Pig), 7/1/39 – Charles M. (Chuck) Jones, dir.). In the previous year, Leon Schlesinger had okayed at least one other unusual project – a sort of cartoon adaptation of the popular Warner live-action jazz/swing musical shorts typically billed as “Broadway Brevities”, which became Hardaway and Dalton’s Katnip Kollege (1938) – complete with borrowed vocal outtakes from live-action feature, Over the Goal. In 1939, an executive decision (Schlesinger’s or some higher-up studio head?) was somehow made to adapt to the cartoon medium a second genre of Warner live-action short, which had been developing increasing notice for a few seasons through its lavish dramatic portrayals and innovative use of three-strip Technicolor – the patriotic historical short. These shorts became a unique signature to Warner’s output in the years before WWII, and were lavishly budgeted and staged (reputedly losing the studio over $1.5 million, yet raking in the prestige of several Oscars). If it could work in live action, why not cartoons? Well, if anyone had actually asked this question, the answer might have been obvious – because truly historical films are not funny. Humorless cartoons telling tales of straight adventure were still a few years away – so the idea of such a project must have seemed to many of the animators like placing the proverbial fish out of water. (Imagine the reaction if such a film had been saddled upon Tex Avery!) As produced, the film takes itself entirely seriously, and (with the possible exception of the independently-produced “The Door” in the final years of Warner cartoon distribution), is the only Warner cartoon ever to contain not so much as a single laugh or chuckle. Accordingly, the project was assigned to the Warner director who, at this time in the fledgling stage of his career, was least associated with laughs and most associated with Disney-quality draftsmanship – Chuck Jones.

In actuality, Jones cannot be credited with true direction of all sequences of this film – as the episode depends more heavily than any other Warner production upon the use of rotoscope imagery from live-action reference footage – presumably produced either on location or in a Warner sound stage outside the periphery of the Termite Terrace lot. Were accurate direction credit known, a host of possible live-action directors might justly deserve their names to be emblazoned upon this short. In fact, sources indicate that several rotoscoped scenes were actually copied out of existing patriotic shorts Warner had already produced, borrowing from its existing film library.

In actuality, Jones cannot be credited with true direction of all sequences of this film – as the episode depends more heavily than any other Warner production upon the use of rotoscope imagery from live-action reference footage – presumably produced either on location or in a Warner sound stage outside the periphery of the Termite Terrace lot. Were accurate direction credit known, a host of possible live-action directors might justly deserve their names to be emblazoned upon this short. In fact, sources indicate that several rotoscoped scenes were actually copied out of existing patriotic shorts Warner had already produced, borrowing from its existing film library.

While original opening credits to date have not been rediscovered, the Blue Ribbon reissue print preserves portions of the opening musical cue over the Blue Ribbon art card, setting the mood with the strains of “Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean”. Several veins of speculation exist among those who attempt to reconstruct the titles of these early films. While chronological breakdown by season would suggest the film could have used the green and yellow rings with “Warner Bros.” lettering on a banner. commonplace to late 1938-39 season releases (see, for example, surviving prints of Snowman’s Land), some have speculated that the more-obviously patriotic red, white, and blue circles with clouds in the center ring (which was about to become the norm for late 1939 and early 1940 Merrie Melodies) was specially-designed for this short, then adapted for general use in the next season. If this is so, then, as recreated on the “Ortitle Buddguddy” Youtube webpage, titling for this cartoon would be unique in the series, as the only cartoon combining use of the red, white, and blue circles with the “Warner Bros,” lettering on a banner (the banner disappeared in the 1939-40 season). Opinion seems unanimous, however, that the fade-in on the waving American Flag in existing prints is faked in post-production in the re-release, and that original prints would have dissolved directly to such animated imagery from the circles, with credits superimposed over the animation. This would mirror the found original ending credits, which superimpose the closing lettering (saying “The End” instead of “That’s All Folks”) over the flag without a fade or dissolve to the rings.

While a young 48-star flag waves majestically atop a mile-high flagpole, a junior Porky Pig (appearing for the first time in three-strip Technicolor and for the first time in color in his slimmer, trimmer, more streamlined form), complete with the unusual highlights (and expense) of light-and-shadow modeling and youthful rosy apple-cheeks, frustrates himself at the foot of the flagpole, having difficulty memorizing the Pledge of Allegiance.

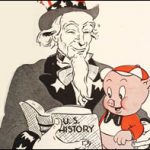

After several failed efforts, he tosses his schoolbook away, muttering as to why he should have to learn the “old pledge of allegiance” anyway. Where he has tossed the book, a transparent image slowly materializes – towering tall in height, and bedecked in red, white and blue stripes and stars on his outfit – the spirit of Uncle Sam. (Animation of this character appears entirely rotoscoped, and it would seem safe to assume that live-action reference footage was shot especially for this production. No actor credit is known for the reference footage, although voice-over work on the finished soundtrack is credited by IMDB to John Deering. My speculation for the reference actor might be Frank McGlynn, Sr., who would appear for the studio in the live-action short “Lincoln in the White House” as Abraham Lincoln in the same year. As the real Porky sleeps, Sam strides over and rouses a transparent “spirit” Porky from the sleeping pig, taking him by the hand off to one side, where both characters solidify. Learning that Porky has no point of reference to understand the phrase “the land of the free”, Sam opens a U.S. History book, and illustrates with historical vignettes how the founding fathers fought back against tyranny, taxes, and “injustice, injustice, injustice”. (Is Porky dreaming, or is this an out-of-body experience?

After several failed efforts, he tosses his schoolbook away, muttering as to why he should have to learn the “old pledge of allegiance” anyway. Where he has tossed the book, a transparent image slowly materializes – towering tall in height, and bedecked in red, white and blue stripes and stars on his outfit – the spirit of Uncle Sam. (Animation of this character appears entirely rotoscoped, and it would seem safe to assume that live-action reference footage was shot especially for this production. No actor credit is known for the reference footage, although voice-over work on the finished soundtrack is credited by IMDB to John Deering. My speculation for the reference actor might be Frank McGlynn, Sr., who would appear for the studio in the live-action short “Lincoln in the White House” as Abraham Lincoln in the same year. As the real Porky sleeps, Sam strides over and rouses a transparent “spirit” Porky from the sleeping pig, taking him by the hand off to one side, where both characters solidify. Learning that Porky has no point of reference to understand the phrase “the land of the free”, Sam opens a U.S. History book, and illustrates with historical vignettes how the founding fathers fought back against tyranny, taxes, and “injustice, injustice, injustice”. (Is Porky dreaming, or is this an out-of-body experience?

Certainly, if it were but a dream, a child with no background in American history could hardly be expected to imagine past events with such historical accuracy!) Patrick Henry, straight out of a past historical short, utters the words “Give me liberty or give me death!” (Pretty heavy stuff for a junior Saturday matinee audience.) Paul Revere rides over hill and dale to summon the minutemen to arms. John Hancock signs the Declaration of Independence. A transparent fife and drum corps ushers in the “Spirit of ‘76.” The liberty bell rings. The Constitution is signed by George Washington. Even a little post-revolutionary history is covered, with brief reference to the pioneers settling the West, and a quote from Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. (The post revolutionary period is touched upon so briefly and abruptly, one almost wonders if the short was originally planned for two reels (the standard running length of the live-action productions), but became too costly as production went along and was cut short to preserve a one-reel length.)

Ultimately, Porky awakens, and now remembers the Pledge of Allegiance by heart, reciting same (minus the now traditional words “Under God”, which were not yet part of the Pledge – curious, in that the quoted language from the Gettysburg Address in the film nonetheless uses the phrase, “Under God”, from which the use in the Pledge probably later derived), as the camera pans back up the mile-long flagpole to the waving flag for the fade-out.

Some stations (particularly Channel 11 in the Los Angeles area) would only unearth this reel for viewing on the 4th of July, as the last cartoon of a half-hour program, never including it in the run of cartoons for everyday viewing. Understandable, as for me, it was quite hard to fathom on my first viewing at a tender age. I remember waiting for the laughs and not finding any, and turning off the TV when the pioneer movement began, thinking the cartoon was going to go on forever. This one-time experiment in dramatic animation becomes more palatable as the age of the viewer advances, and today I can view same as a milestone of detail for a Warner cartoon, resplendent in its lighting and color choices, and probably intended by the Studio heads to shoot for an Oscar berth. Unfortunately, it did not secure even a nomination (while the rival, nearly as serious epic from MGM, Peace on Earth, preaching the opposite message of peace, not war, did). Most importantly, if the reaction of children in the original audience was anything like my first viewing experience, the production likely missed entirely its target demographic, failing to create a new generation of junior patriots. (I seriously wonder if the cartoon would even have received favorable reaction amidst a boy scout convention.) All in all, studio executives both within the Schlesinger studio and Warner’s own board rooms likely judged the experiment a disappointment – its like would never be repeated. However, the film may be viewed as having some lasting legacy. It possibly paved the way for Paramount’s unexpected green-lighting of a serious animation project in the form of the Fleischer Superman series in the early 1940’s. And, decades later, it can be seen as the predecessor and foundation for DIC’s television experiment, Liberty’s Kids, and for other serious historical treatments in Mister Magoo and Animaniacs episodes, to be discussed later in these articles.

Holiday Highlights (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 10/12/40 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.), a spot-gag romp through the calendar pages, includes a bit for Washington’s birthday. Young George chops down the cherry tree, augmenting such action by yelling, “Timberrrrr!!” Papa Washington asks him man to man if he didst chop down yon cherry tree, and George, producing his hatchet, replies in a colonial version of Artie Auerbach’s old catch phrase, “Ummmmm, Couldst be!”

Hysterical Highspots in American History (Lantz/Universal, 3/31/41- Walter Lantz, dir.), is one of the studio’s few attempts to replicate the “spot gag” reel format that Tex Avery had made so recurring at Warner Brothers, with gags on American history up to the then-present day. The revolution is represented with three short sequences. As Paul Revere darts through village and farm with his call to arms, two old crones (replicating the characters of Brenda and Cobina, originally portrayed by Blanche Stewart and Elvia Allman on Bob Hope’s Pepsodent radio show – they can also be seen on screen in the Three Stooges’ feature, Time Out For Rhythm (1941)) react at word of the redcoats with “Look. MEN!!” They clamor downstairs from their apartments, and toss into the street a large sawhorse from which is hung a “Detour” sign pointing into their doorway (also including in small letters below, “W.P.A.”, the controversial work program later declared unconstitutional). The minutemen are depicted with a sleepy loafer who, when called to arms, responds in mumbles provided by Mel Blanc using his Hugh Herbert impression, “Wait a minute. Now, just a minute. Just gimme one minute”, then snaps out of it with, “WHAT AM I SAYING???” Finally, George Washington is shown being the “first man to toss a silver dollar across the Potomac”. His troops dive after it, trampling him, as the announcer concludes the thought, “…and the last.” As a final coda, over a century and a half later, as WWII conscription commences, the same two old crones, now even more decrepit, still shout, “Look. MEN!”, and repeat the same Detour sign ploy to lure their prey.

Hysterical Highspots in American History (Lantz/Universal, 3/31/41- Walter Lantz, dir.), is one of the studio’s few attempts to replicate the “spot gag” reel format that Tex Avery had made so recurring at Warner Brothers, with gags on American history up to the then-present day. The revolution is represented with three short sequences. As Paul Revere darts through village and farm with his call to arms, two old crones (replicating the characters of Brenda and Cobina, originally portrayed by Blanche Stewart and Elvia Allman on Bob Hope’s Pepsodent radio show – they can also be seen on screen in the Three Stooges’ feature, Time Out For Rhythm (1941)) react at word of the redcoats with “Look. MEN!!” They clamor downstairs from their apartments, and toss into the street a large sawhorse from which is hung a “Detour” sign pointing into their doorway (also including in small letters below, “W.P.A.”, the controversial work program later declared unconstitutional). The minutemen are depicted with a sleepy loafer who, when called to arms, responds in mumbles provided by Mel Blanc using his Hugh Herbert impression, “Wait a minute. Now, just a minute. Just gimme one minute”, then snaps out of it with, “WHAT AM I SAYING???” Finally, George Washington is shown being the “first man to toss a silver dollar across the Potomac”. His troops dive after it, trampling him, as the announcer concludes the thought, “…and the last.” As a final coda, over a century and a half later, as WWII conscription commences, the same two old crones, now even more decrepit, still shout, “Look. MEN!”, and repeat the same Detour sign ploy to lure their prey.

Aviation Vacation (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 8/2/41 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.) – includes still images of George Washington on the side of Mt. Rushmore, and the other three Presidents = plus a newly-carved cliff with a split screen for the upcoming election, allowing your choice between the Democrat and the Republican. (Further Mt. Rushmore references will not be included in this article – excepting all four faces reacting in fright upon meeting the Addams Family in the title sequence of their 1973 Hanna-Barbera cartoon incarnation.)

Aviation Vacation (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 8/2/41 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.) – includes still images of George Washington on the side of Mt. Rushmore, and the other three Presidents = plus a newly-carved cliff with a split screen for the upcoming election, allowing your choice between the Democrat and the Republican. (Further Mt. Rushmore references will not be included in this article – excepting all four faces reacting in fright upon meeting the Addams Family in the title sequence of their 1973 Hanna-Barbera cartoon incarnation.)

Scrap Happy Daffy (Warner, Looney Tunes (Daffy Duck), 8/21/43 – Frank Tashlin, dir.) pits Daffy against the latest Nazi secret weapon – a tin-can eating billy goat, bent on devouring Daffy’s wartime scrap pile for Der Fuehrer. The goat proves a tough customer, and Daffy is down for the count, wishing he had a can of spinach about now. Suddenly, a beam of light spotlights Daffy from the heavens, and Daffy receives a visitation from the patriotic spirits of his ancestors from the past – a pilgrim (great great great uncle Billingham Duck) who landed on Plymouth Rock; a revolutionary war duck in powdered wig who fought with Washington at Valley Forge; a pioneer duck who explored with Daniel Boone and got scalped; a sailor duck who sailed with John Paul Jones; and finally, a duck who appears to have himself been the avian Abraham Lincoln! They each shame Daffy for his despair, and attempt to inspire him with a ditty set to the tunes of Yankee Doodle and Battle Hymn of the Republic, entitled “Americans Don’t Give Up.” A rejuvenated Daffy rises to the occasion, and, donning a cape and a suit of tights with a large “A” on the chest, transforms into “Super American”. Soaring through the air, he butts the goat for a loop, twisting his horns into circles resembling glasses. Shells fired from a Nazi support sub bounce off Daffy’s chest. Daffy ties the barrel of the sub deck gun into a pretzel knot. As the sub submerges, Daffy holds it captive by grabbing the periscope. At this impossible moment, the scene dissolves back to Daffy’s scrap yard, where Daffy is in actuality tugging on a water pipe in the ground, which squirts him in the face to awaken him. “A dream! It was all a dream”, says Daffy. But from atop his massive pile of tin cans comes the call of a chorus of voices: “Hey!” Panning upwards, the camera reveals the goat and the damaged Nazi sub, now the latest addition to the scrap pile, with the sub crew stating in unison, “Next time you dream, include us out!”

Bored of Education (Paamount/Famous, Little Lulu, 3/1/46 – Bill Tytla, dir.) – A typical day at school finds Lulu and Tubby in a war of pranks on each other while history class is in session. Lulu is called upon by the teacher, and gets stuck in answering history questions, with Tubby feeding her all the wrong dates for events – so that she gets the dunce cap and has to spend class in the corner studying her history. Lulu dozes off and enters a dream fantasy where she chases Tubby through the pictures of a giant history book, Tubby all the while assuming the guises of famous historical figures to avoid detection. In the revolutionary War period, Tubby first appears in the role of Paul Revere. While his shouts that the British are coming appear in earnest, Tubby has chosen the wrong steed for the occasion – a swayback old junkman’s horse, who is three times slower than the glue factory candidate from Popeye’s “Her Honor, the Mare”. Though Tubby pleads for the horse to go faster, the horse replies that if he could go any faster, he’d be in the Kentucky Derby. Lulu solves Tubby’s need for speed by fastening skyrockets to the horse’s rear end and lighting the fuse – causing the villages and farms to be visited with the speed of a streaking comet. Suddenly the background under Lulu transforms from flat to a pinnacle, as a sign sprouts from the ground reading “Bunker Hill”. From nowhere, Lulu produces a musket to ready herself for the attack. On cue, the redcoats advance – or should I say, redcoat, being just Tubby. Before Lulu can draw a bead on him, Tubby cautions, “Don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes.” To ensure this never happens, Tubby dons a pair of dark sunglasses. But quick-witted Lulu is again one step ahead of him, and begins to slurp on a triple-sized ice cream cone. Tubby isn’t called that for nothing, and his calorie cravings get the better of him, with his eyes bulging out of their sockets, popping the sunglasses right off his face. With plenty of white now visible, ice cream cone is replaced by musket once again, and Tubby beats a strategic retreat amidst a hail of musket shot.

The Little Cut-Up (Paramount.Famous, Novelroon, 1/21/49. I. Sparner, dir.) is a rather forgotten film, pretty strictly for the younger set, with only a few smiles and no belly laughs. The film opens on a tree in the forest, populated by a variety of creatures, including a wise owl, three squirrels who take turns whacking each other on the head to crack nuts to eat, a mama bluebird and her three fledglings, and a Mr. and Mrs. Bunny, the latter of whom is knitting little things – quite a few of them – for an expectant family. Nearby, a community of beavers busies themselves on a nearly-completed dam. Along comes a little boy dressed in clothes suggesting colonial times, and a small white-powdered wig. He is carrying a small hatchet and singing the latest ditty Winston Sharples was pushing, probably titled “Chop Chop Chop”, and having fun cutting down small trees at random. Of course, the animal community tree turns out to be in the line of fire, and with a few well-places blows, the child fells it, causing it to land squarely on the beaver dam. (Damn!) Everyone’s homes and property are a wreck, and wise owl emerges from the stream covered in mud, and shames the boy for the destruction he’s caused. Learning that everyone’s homeless, the child decides to make amends by taking them to his home and building them all new domiciles. At a sumptuous plantation, the boy builds wise owl a colonial-style treetop structure, complete with a rocking chair on the veranda. Mrs. Bluebird gets an equally ornate birdhouse on a pole, with a small fountain alongside for her brood to use as a birdbath. The squirrel’s home has made life easier by the addition of a nut bowl and nutcracker. A larger house serves as a hutch for the rabbits – and they can use the space, as they now have a stroller built for over a dozen babies, with a descending bar over the top that lowers a row of milk bottles when it’s feeding time. As for the beavers, the child puts his hatchet to more constructive use, chopping a sturdy cherry tree to give the beavers a strong lumber supply for their new dam. A colonial gentleman armed with a musket – the boy’s father – hears the tree fall, rushes to the scene, and places blame on the beavers for felling the best cherry tree in Virginia. The boy stands in front of the raised musket barrel to block the shot, and states – – well, you should know the rest, as the boy is of course, the young George Washington.

The Little Cut-Up (Paramount.Famous, Novelroon, 1/21/49. I. Sparner, dir.) is a rather forgotten film, pretty strictly for the younger set, with only a few smiles and no belly laughs. The film opens on a tree in the forest, populated by a variety of creatures, including a wise owl, three squirrels who take turns whacking each other on the head to crack nuts to eat, a mama bluebird and her three fledglings, and a Mr. and Mrs. Bunny, the latter of whom is knitting little things – quite a few of them – for an expectant family. Nearby, a community of beavers busies themselves on a nearly-completed dam. Along comes a little boy dressed in clothes suggesting colonial times, and a small white-powdered wig. He is carrying a small hatchet and singing the latest ditty Winston Sharples was pushing, probably titled “Chop Chop Chop”, and having fun cutting down small trees at random. Of course, the animal community tree turns out to be in the line of fire, and with a few well-places blows, the child fells it, causing it to land squarely on the beaver dam. (Damn!) Everyone’s homes and property are a wreck, and wise owl emerges from the stream covered in mud, and shames the boy for the destruction he’s caused. Learning that everyone’s homeless, the child decides to make amends by taking them to his home and building them all new domiciles. At a sumptuous plantation, the boy builds wise owl a colonial-style treetop structure, complete with a rocking chair on the veranda. Mrs. Bluebird gets an equally ornate birdhouse on a pole, with a small fountain alongside for her brood to use as a birdbath. The squirrel’s home has made life easier by the addition of a nut bowl and nutcracker. A larger house serves as a hutch for the rabbits – and they can use the space, as they now have a stroller built for over a dozen babies, with a descending bar over the top that lowers a row of milk bottles when it’s feeding time. As for the beavers, the child puts his hatchet to more constructive use, chopping a sturdy cherry tree to give the beavers a strong lumber supply for their new dam. A colonial gentleman armed with a musket – the boy’s father – hears the tree fall, rushes to the scene, and places blame on the beavers for felling the best cherry tree in Virginia. The boy stands in front of the raised musket barrel to block the shot, and states – – well, you should know the rest, as the boy is of course, the young George Washington.

Next Time: Never underestimate the efforts of a patriotic rabbit!